Sharpening

A dull knife is more dangerous than a sharp one. You push harder, it slips, you cut yourself. The tool fights you instead of helping you.

Sharpening isn’t separate from the work. It’s part of the work.

Toshio Odate’s 1984 book Japanese Woodworking Tools describes the shokunin tradition. The word doesn’t mean “craftsman.” It means someone who polishes both technique and heart through daily practice.

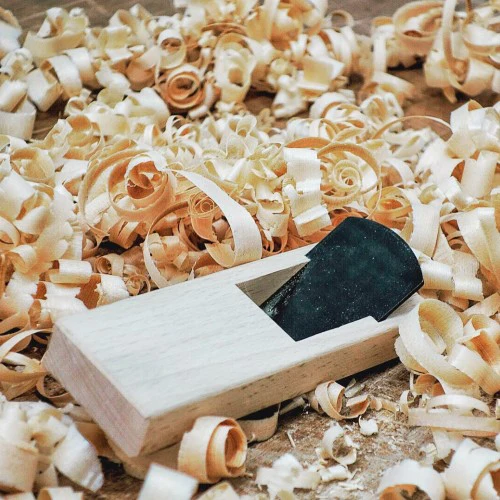

Japanese woodworkers treat tools as extensions of the hand. Chisels are laminated steel with hollow-ground backs. Saws cut on the pull stroke. Planes leave glass-smooth surfaces. Each requires constant attention — cleaning, oiling, sharpening on waterstones.

The discipline isn’t lost productivity. It’s the foundation for everything that follows.

Odate writes: “The Shokunin has a social obligation to work his best for the general welfare of the people. This obligation is both spiritual and material.”

The spiritual part matters. You can’t do fine work with dull instruments. The saw that cuts true. The chisel that pares cleanly. The plane that doesn’t tear grain. These aren’t givens — they’re earned through daily maintenance.

The pattern extends beyond physical tools:

- The codebase that’s been refactored stays easy to change

- The notes that are organized stay useful

- The relationship that’s maintained stays strong

Entropy is constant. Maintenance is the only counter. The amateur wants to skip to the exciting part. The professional knows the work of preparation is the work.